On 22 May 2025 the UK and Mauritius signed the Agreement between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of the Republic of Mauritius concerning the Chagos Archipelago including Diego Garcia (Chagos Archipelago Agreement), which will enter into force following completion of the respective domestic procedures and notification of the other Party (Art 18). The UK requires amended primary and secondary legislation, while it is estimated the required Mauritian Ministerial decisions will take less than 6 months (Explanatory Memorandum, pp. 11-12).

From a UK perspective, “The purpose of the treaty is to secure the long-term, secure and effective operation of the UK-United States of America (US) military base on Diego Garcia, which is critical for the UK’s national security; to ensure legal certainty over the operation of the Base while respecting partners’ interests; and to uphold the international rule of law” (Explanatory Memorandum, p.2; US State Department). The UK believed the sustainability of the UK operation of the Base was at significant risk, including most notably as a result of the decisions of international courts and tribunals, including the International Court of Justice, relating to the Chagos Archipelago (Chagos Archipelago Agreement, Preamble) and the foreseeability of a future binding decision upon the UK. “Sovereignty was also routinely challenged in the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission, which carried risk of legal challenge leading to an ICJ judgment” (Explanatory Memorandum, p. 3; see further IOTC Agreement, Art 23, which might e.g. be raised in disputes on ‘coastal State’ membership, Art 4). Tellingly, this matter is addressed in Article 8 and the Exchange of Letter on the Interpretation of Article 8 of the Chagos Archipelago Agreement (22 May 2025), which provides that upon entry into force, among others, the UK confirms its membership of the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) in respect of Chagos Archipelago transfers to Mauritius and the UK will not claim ‘Coastal State’ but ‘Distant Water Fishing Nation’ membership status at IOTC. The Explanatory Memorandum also made it clear that Mauritius made “frequent public commitments to continue pursuing its legal campaign to secure a binding judgment. The UK government of the day (and all subsequent governments) recognised that there were multiple pathways by which Mauritius could achieve this”.

From a Mauritius perspective, the Chagos Archipelago Agreement “recognises the sovereignty of Mauritius over the entirety of the Chagos Archipelago, including Diego Garcia […] [and] marked a significant step in the completion of the decolonisation process of Mauritius” (Prime Minister Navinchandra Ramgoolam’s Remarks; Chagos Archipelago Agreement, Preamble). Recognising the “wrongs of the past”, the Chagos Archipelago Agreement shall address the past treatment of Chagossians and their continuing welfare.

The Chagos Archipelago Agreement is designed as a comprehensive agreement in ‘full and final resolution of the differences’ related to the Chagos Archipelago and therefore addressed an array of ocean governance issues. A unique compulsory dispute settlement procedure by arbitration, which can only be triggered by the UK, is provided in Article 15(4)-(5) and Annex 4 concerning disputes on if a ground for termination exists and the dispute cannot be resolved by other means. A non-exhaustive selection of key provisions for ocean governance is provided below:

Article 1 Sovereignty

Chagos Archipelago Agreement (2025)

Mauritius is sovereign over the Chagos Archipelago in its entirety, including Diego Garcia.

Article 2 Authorisation in respect of Diego Garcia

1. As sovereign, Mauritius authorises the United Kingdom to exercise the rights and authorities of Mauritius with respect to Diego Garcia in accordance with the terms of this Agreement.

2. The authorisation under paragraph 1 shall comprise all rights and authorities that the United Kingdom requires for the long-term, secure and effective operation of the Base, including for the Defence and Security Requirements, Conditions and Procedures in Annex 1 and the Jurisdiction and Control Arrangements in Annex 2.

3. Mauritius retains title over the land and the territorial sea of Diego Garcia, including the seabed and subsoil, as well as all rights and authorities not authorised under paragraphs 1 and 2, including:[…]

f. sovereignty over natural resources, including fisheries;

g. conservation and protection of the environment, including the marine environment;

Article 3 Defence and Security

1. The Parties agree to the Defence and Security Requirements, Conditions and Procedures in Annex 1 […]

3. The Parties shall cooperate on matters relating to maritime security, including trafficking in narcotics, arms and persons, people smuggling and piracy.

Article 5 Environment

1. The United Kingdom shall exercise the rights and authorities under Article 2 in accordance with applicable international law on environmental protection, and with due regard to applicable Mauritian environmental laws.

2. The United Kingdom agrees to provide support and assistance to Mauritius in the establishment and management of its Marine Protected Area in the Chagos Archipelago, in accordance with terms to be agreed between the Parties by a separate written instrument.

3. The Parties shall cooperate on other matters relating to the protection of the environment, including in relation to oil and other spills, and illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

Article 8 International Organisations

1. The United Kingdom agrees to ensure its membership in international organisations is consistent with Article 1.

Article 12 Joint Commission

A Joint Commission to facilitate the implementation of this Agreement shall be established. The composition, functions and procedures of the Joint Commission are set out in Annex 3 [which provides for a composition of UK and Mauritius representatives, with the USA having observer status].

Article 19 Definitions

For the purposes of this Agreement: […]

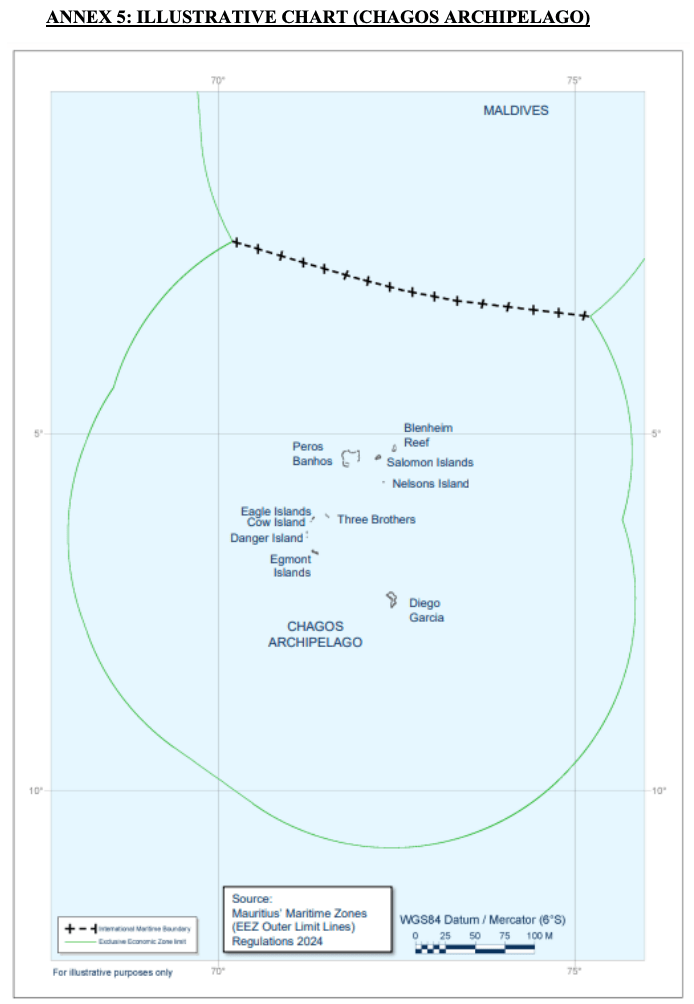

“Chagos Archipelago” means the islands, including Diego Garcia, and maritime zones of the Chagos Archipelago, including the internal waters, territorial sea, archipelagic waters and the exclusive economic zone, and the airspace above and seabed and subsoil below [without prejudice to Mauritius’ claims in respect of the continental shelf].

“Diego Garcia” means the island of Diego Garcia and a twelve (12) nautical mile zone surrounding the island of Diego Garcia, and includes the airspace above and seabed and subsoil below.

Annex 1: Defence And Security Requirements, Conditions And Procedures

Diego Garcia

1. In accordance with this Agreement and with reference to Article 2(5) and Annex 2, in respect of Diego Garcia, Mauritius agrees the United Kingdom shall have:

a. unrestricted access, basing and overflight for United Kingdom and United States of America aircraft and vessels to enter into the sea and airspace of Diego Garcia;

b. unrestricted ability to: […]

v. authorise the installation, operation and repair of new and existing communication systems and electronic systems and associated cables; […]

viii. permit access, basing and overflight for non-United Kingdom and non-United States of America aircraft and vessels, upon notification to Mauritius; and

ix. manage, use and develop the land and surrounding waters and seabed for defence purposes. This excludes the construction of any artificial islands.

Chagos Archipelago beyond Diego Garcia

3. In accordance with this Agreement, in respect of the Chagos Archipelago beyond Diego Garcia, Mauritius agrees:

a. vessels and aircraft of the United Kingdom and the United States of America shall have unrestricted rights of overflight, navigation and undersea access. States operating with the United Kingdom or the United States of America shall also have such unrestricted rights, save in respect of overflight or undersea access, which require notification;

b. the United Kingdom shall have rights of access for maintenance and upgrades of equipment, following notification to Mauritius, after having advised Mauritius of the location of all such equipment; […]

f. between twelve (12) and twenty-four (24) nautical miles surrounding the island of Diego Garcia, Mauritius and the United Kingdom shall jointly decide on the construction or emplacement of any maritime installation, sensor, structure or artificial island.

Mauritian Security Review

4. Before approving or proceeding with a proposal for:

a. the construction or emplacement of any maritime installation, sensor, structure or artificial island in an area beyond the twenty-four (24) nautical miles surrounding the island of Diego Garcia; or

b. any proposal for development in the land territory of the Chagos Archipelago beyond Diego Garcia, Mauritius shall conduct a Security Review in accordance with paragraph 6 [which provides for information exchanges with the UK, as well as possible decision making by the Joint Commission. An emerging risks procedure is also found in para 7].

11. For the purposes of this Annex:

a. “access” refers to the grant of rights or permissions which would not otherwise exist in international law. Nothing in this Agreement modifies or affects any rights, including rights of overflight or navigation, which exist as a matter of international law;

b. “Chagos Archipelago beyond Diego Garcia” means any area within the Chagos Archipelago that is beyond Diego Garcia;

c. “unrestricted” means not requiring permission or notification, subject to the standing authorisations and notifications separately agreed between the Parties to meet the requirements of international or domestic Mauritian law or current practice.

Annex 2: Jurisdiction And Control Arrangements

Mauritian criminal jurisdiction

3. On Diego Garcia, Mauritius shall exercise all prescriptive, enforcement and adjudicative criminal jurisdiction conferred on it by its laws in relation to allegations against […]

b. all persons not connected to the operation of the Base, including persons involved in offences relating to unlicensed commercial fishing and the trafficking in arms or narcotics.

Cooperation in the exercise of criminal jurisdiction

8. In order to support the exercise of jurisdiction by Mauritius on Diego Garcia, the United Kingdom agrees to provide assistance to Mauritius in: […]

e. the prevention of unlicensed commercial fishing, and trafficking of arms, persons and narcotics and illegal migration.

Miscellaneous

15. Mauritius shall exercise criminal and civil jurisdiction in respect of activities such as irregular migration and unlicensed commercial fishing, provided such exercise of jurisdiction is in conformity with the requirements of this Agreement.

Finally, the signing of the Chagos Archipelago Agreement was accompanied by the signing of a new Strategic Partnership Framework. Among other items, it will address:

- Deepening cooperation on maritime security and irregular migration in areas such as “irregular migration, drugs trafficking, piracy, and illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing”. This will include “Cooperation agreements and capacity building to secure Mauritius’s Exclusive Economic Zone; Consideration of patrolling capability across the Chagos Archipelago to support a secure maritime domain; Cooperation to counter and manage irregular migration; and Provision of training and institutional partnerships to boost Mauritian maritime security capability and strengthen fisheries protection”.

- Cooperation in addressing climate change. This will include “Mitigation and adaptation projects to tackle the immediate effects of climate change including coral restoration, coastal erosion and indigenous species conservation; and Technical expertise to develop and manage the Chagos Archipelago Marine Protected Area, pursuant to the agreement on the exercise of sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago”.

For further information, see previous reporting.